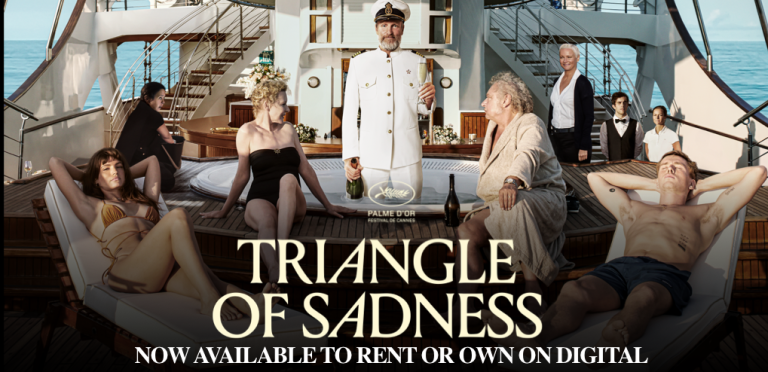

Triangle of Sadness is the latest noteworthy film from Swedish director Ruben Östlund, following his acclaimed work The Square. This marks his second Palme d’Or win at the Cannes Film Festival, a rare and impressive feat.

This film isn’t exactly an easy watch, nor is it particularly difficult. It’s a dark comedy rooted in satire, with a relatively straightforward and accessible plot, but one that weaves in layers of profound, far-reaching commentary. Östlund masterfully threads critiques of capitalism, consumerism, gender inequality, class division, and racial prejudice into a deceptively simple narrative. The result is something that never feels overwhelming—just smart, sharp, and deeply resonant.

Note: Spoilers ahead

The story begins with two central characters: Carl, a handsome young male model in the early stages of his career, and his girlfriend Yaya, also a model and social media influencer. The couple boards a luxury cruise reserved for the ultra-wealthy, mingling with the world’s elite. But when pirates attack the yacht, Carl, Yaya, and a handful of survivors wash ashore on a deserted island—and that’s when the real story begins.

Early Tensions: Beauty, Money, and Gender Roles

Even before things go off the rails, Triangle of Sadness explores gender imbalance. Carl is portrayed not just as a stereotypical “dumb pretty boy,” but also as someone acutely aware of male gender inequality. In an early restaurant scene, he repeatedly questions why Yaya never offers to pay the bill—even though money isn’t an issue for either of them. It’s as if in high society, men paying is so deeply ingrained that no one questions it anymore. Visually, the film reinforces this disconnect: the two characters aren’t even in the same frame while dining, a subtle cinematographic cue to their ideological divide.

Act 1: Carl and Yaya

The first part of the film focuses on Carl and Yaya’s relationship, highlighting their imbalances and interpersonal conflicts. When they step onto the yacht, we smoothly transition into the second act: The Yacht.

Act 2: The Yacht

Now immersed in the opulence of the super-rich, Carl continues to feel insecure—especially when Yaya flirts with a young sailor. But gender dynamics soon give way to a broader theme: social hierarchy. After Carl complains to yacht management, the sailor is promptly fired. This yacht caters to the whims of the ultra-wealthy, where even absurd demands are treated as commands.

This part of the film echoes themes from The Menu, where elites are served gourmet experiences on a remote island. But Triangle of Sadness arguably does a better job portraying its upper-class characters. Though they hail from different parts of the world—mostly the US and Europe—they all rose through capitalism. Unlike the arrogant and caricatured guests in The Menu, these ones appear polished and educated, truly embodying the modern elite.

The Turning Point: The Captain’s Dinner

The shift comes during the captain’s grand dinner, meant to impress. But when a storm hits, this lavish gathering spirals into absolute chaos. Guests start vomiting, defecating, and collapsing in the once pristine luxury environment. The social elite are reduced to helpless, grotesque beings. Despite their wealth and status, nature strips them bare—revealing just how fragile and human they really are.

This intense, absurd, and nauseating sequence is arguably the second act’s climax. It’s raw, unfiltered, and one of the most daring depictions of class satire in recent cinema. Some theaters reportedly handed out barf bags to audiences—yes, it’s that visceral.

Amid the chaos, a brilliant conversation unfolds between the ship’s captain and a wealthy Russian tycoon. They toss back quotes from famous figures, critiquing capitalism and socialism alike:

“Never argue with stupid people. They will drag you down to their level and beat you with experience.” – Mark Twain

“Socialism only works in heaven, where they don’t need it, or in hell, where they’ve already got it.” – Ronald Reagan

“Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of a cancer cell.” – Edward Abbey

“The problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other people’s money.” – Margaret Thatcher

“The last capitalist we hang shall be the one who sold us the rope.” – Karl Marx

“The strongest single force in the world is a longing for freedom and independence.” – John F. Kennedy

“Freedom in capitalist society always remains about the same as it was in ancient Greek republics: freedom for slave owners.” – Vladimir Lenin

Act 3: The Island

Just when you think the chaos has peaked, the film shifts into its third act: The Island. After the yacht is attacked by pirates, the remaining passengers—including Carl and Yaya—wash ashore a deserted island and must learn to survive.

One darkly humorous twist comes when a wealthy British couple, who made their fortune selling weapons, are blown up by a grenade—possibly one they themselves manufactured. A biting jab at the military-industrial complex.

Enter Abigail: The New Power

On the island, Abigail—a previously invisible Filipino cleaning lady from the yacht—emerges as the group’s savior. She knows how to fish, cook, and start fires. Suddenly, social capital means nothing. Wealth, beauty, fame, and intellect are useless in survival. The real power lies with labor and practical skills.

From janitor to queen, Abigail quickly becomes the group’s new leader. And with power comes corruption. The satire shifts from capitalism to socialism. Abigail, now the “captain” of this working-class commune, begins abusing her newfound authority.

Power, Gender, and Sex Reversed

One of the film’s boldest reversals is Carl’s transformation from aloof male model to a “boy toy” for Abigail. To secure food, he has to satisfy her physically. Yaya, disturbed but powerless, has no choice but to accept the arrangement. In a twisted play on sex work, the roles are inverted: the buyer is a lower-class woman, the seller is a middle-class man. It’s transactional, it’s survival—and it’s brutally honest.

No Climax, Just a Slow Burn

Unlike the explosive chaos of the second act, the third is more restrained. The interest lies in watching societal roles collapse: wealth, beauty, race, gender—all shuffled and flipped. The absurdity doesn’t need to scream; it simmers.

The ending? Ambiguous and chilling. Yaya discovers a luxury resort on the island—salvation, it seems. But Abigail hesitates. She knows what returning means: going back to a life where she’s invisible, poor, unimportant. Here, she has power, a young man at her beck and call, and control over her fate.

As Yaya walks ahead, unaware, Abigail lifts a large rock. The film cuts away. We don’t see what happens. Instead, we see Carl running through the forest, terrified and bleeding. Did he hear Yaya scream? Did Abigail attack him too? Or is he running from the truth? The audience is left to imagine the ending themselves.

A Savage, Brilliant Social Satire

Triangle of Sadness pulls off something rare: a smart, hilarious, and disturbing political satire that’s both accessible and layered. It deconstructs our societal structures—class, gender, race—and reduces everything to our primal needs: food, safety, sex, survival.

In this raw, primitive society, those who know how to work and survive become the new leaders. And once those needs are met, power inevitably begins to take root again—planting the seeds of inequality that plague our modern world.

In a time when the top 1% own 38% of the world’s wealth, and the poorest 50% hold less than 2%, Triangle of Sadness is a brilliantly twisted comedy about the cruel absurdity of our current social systems. It forces us to laugh—then look around, and maybe, just maybe, reconsider what we value most.