Early in 2019, Netflix released the TV series Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, based on the book of the same name by journalist Stephen Michaud. Despite his revulsion at Ted’s crimes, Michaud dove into the case like a young reporter chasing the most sought-after figure in the media at the time. When Ted first met Michaud, his attitude screamed, “Why should I bother talking to you?” But eventually, as Michaud put it, Ted “embraced the tape recorder like it was his own” and began spilling his entire story. It was the final confession of a man already sentenced to two death penalties.

“I’m not an animal, I’m not crazy, and I don’t have multiple personalities.” – Ted Bundy

The Crimes of Ted Bundy

The 1970s in the United States were a turbulent era. It was a brief “pause” between phases of the Cold War, marked by anti-Vietnam War protests and a rising plague: serial killings. Before Ted Bundy, there were notorious figures like Jack the Ripper, the Zodiac Killer, and the infamous Charles Manson. Yet, the FBI and American police were still largely in the dark about this type of criminal. It wasn’t until Ted Bundy emerged, with a spree of crimes that outraged the public, that the term “serial killer” was coined—and the FBI began developing a system to study the psychology of such offenders.

It all started with Ted Bundy.

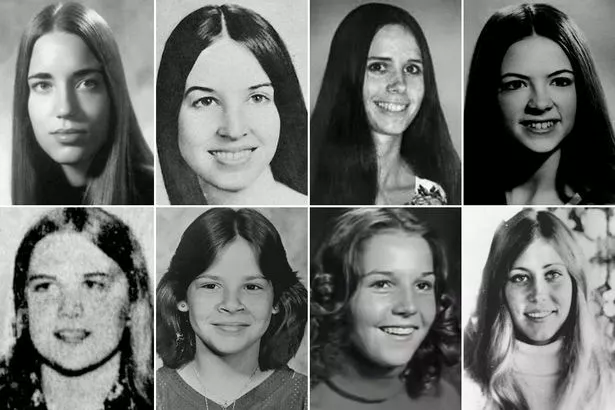

The story kicked off in 1974 in Washington County, Oregon—a quiet Midwestern pocket of America—where young women began mysteriously vanishing. Most were local college students. Though there were clues, the police couldn’t explain the disappearances or locate the missing women.

In just seven months, nine women vanished in Oregon alone.

While Oregon police hunted for answers, similar cases cropped up in Utah, Colorado, and Idaho. Back then, each state’s police operated independently, and the FBI wasn’t yet involved, making investigations disjointed and slow. Authorities couldn’t even confirm if these were criminal cases—or if they shared a single culprit.

Witnesses reported that, before vanishing, victims were approached by a man with his arm in a cast, asking for help carrying items to his car. He introduced himself as “Ted.” Despite these leads, police couldn’t pin down this “Ted.” It was just a nickname, and no solid evidence tied him to the crimes.

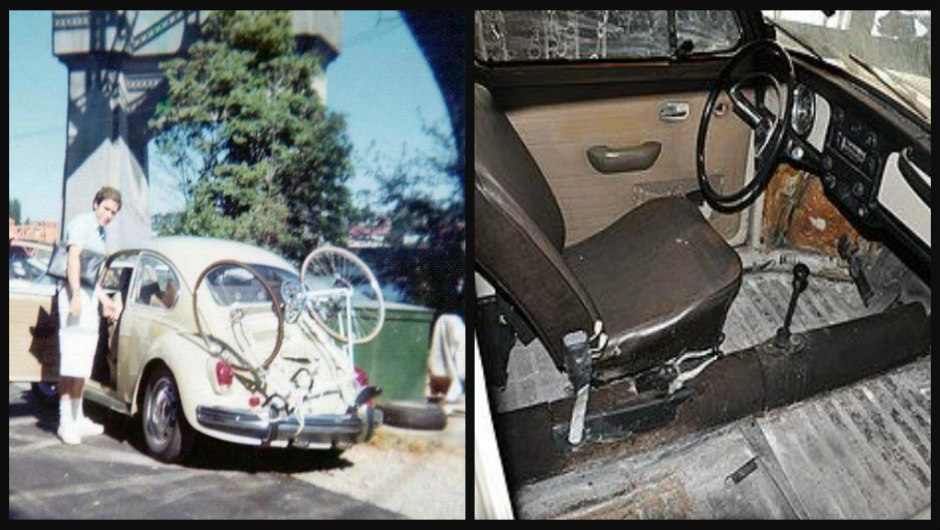

After a failed attack and a tip from his girlfriend about suspicious behavior, Theodore Bundy—a charming, well-spoken young man with a psychology degree, active in social circles, and on the cusp of graduating law school in Utah—was arrested on suspicion of murder. His capture was sheer luck: a Colorado patrol officer spotted a Volkswagen driving at night without headlights. When he signaled it to stop, the car fled. After a hours-long chase, he pulled the driver over and found incriminating items inside.

Colorado police followed the trail to Taylor Mountain, a rugged wilderness area. There, they uncovered victims’ bodies—dumped by Ted and ravaged by wildlife, leaving little behind. Taylor Mountain was remote, thick with thorny brush, which let Ted conceal the corpses for years unnoticed.

If the story had ended there, Ted Bundy might not have become such a terrifying legend. At that point, his name only stirred fear in a few Midwestern states. But Colorado police failed their duty, letting Ted escape custody twice. After the second breakout, he vanished.

Three years later, in 1978, a shocking crime rocked Florida’s Chi Omega sorority house. Two female students were brutally raped and murdered in their sleep; three others were attacked similarly but survived.

As police swarmed Chi Omega, assuming the killer had fled, another identical attack occurred practically across the street. By the time they arrived, the perpetrator was long gone.

This time, the FBI stepped in. Florida police linked up with Colorado authorities, uncovering striking similarities in methods and behavior. Ted Bundy was arrested again and charged with serial murder under Florida law.

Ten Years of Prosecution and Ted Bundy’s Fearsome Persona

Ted Bundy wasn’t just terrifying for his murders and ability to evade justice. He was a psychology graduate nearing a law degree, climbing into America’s middle class with strong social ties and political ambitions. This gave him a cunning intellect, a perfect façade, and a silver tongue—making it maddeningly hard to convict him.

When evidence was thin, Ted—despite being the nation’s most hated suspect—spoke to the press with the swagger of a presidential candidate, not a killer. He grinned, waved to reporters, vowed to “win at trial” (framing it like a lawyer’s triumph rather than a plea of innocence), and railed against the U.S. justice system (like a politician vying for office).

At trial, Ted rejected his lawyer’s advice to plead guilty for a life sentence instead of death. He represented himself, cross-examining witnesses like a seasoned attorney and jabbing his finger at the jury. It’s hard to imagine a killer so smugly confident. He showed no remorse or fear—just treated it like a game.

Throughout the prosecution, Ted wielded psychological tricks to toy with prosecutors and jurors: refusing to give his real name when first arrested in Florida, dismissing shaky evidence, decrying the justice system to the press, mocking bite-mark evidence with quips like “convicting someone for crooked teeth,” even proposing marriage on sentencing day. It all showcased his exceptional intelligence—so much so that the judge, after sentencing him to death, admitted Ted could’ve been a brilliant lawyer without his heinous acts.

Another chilling trait was his coldness. At his first death sentencing, as the judge delivered the verdict, Ted stayed calm, even winking at the camera. But at the second, his demeanor flipped. After losing, he lunged at the prosecution. If he wasn’t fazed the first time, why the outburst the second? Ted didn’t fear death—he hated losing. That’s why the second death sentence sparked such fury.

Decoding Ted Bundy’s Recorded Confessions

Later, with death looming, Ted got a chance to recount his life and crimes to journalists. For him, it was a rare shot to reconnect with the outside world and reclaim the spotlight. He famously said, “I don’t care how you write about me—I just want it to sell.”

When criminologists tackled Ted’s case, they struggled to pinpoint his motives. He didn’t come from poverty or a life that drove him to crime. He wasn’t a violence junkie with a rap sheet, nor a bloodthirsty sadist who tortured animals as a kid. His mental health seemed normal—no religious zeal or Beatles-obsessed delusions like Charles Manson. Experts found no clear trigger beyond his heavy consumption of pornography. But could that alone turn a middle-class psychology grad and law student into a deranged killer?

In the tapes, Ted painted his childhood as idyllic—a perfect family, playing with town kids, a lively school life with sports, friends, and admiration.

Reality begged to differ. His sister later described him as a loner. Growing up poor in a rundown neighborhood, Ted stuttered, earning mockery and isolation from local kids. School was no better. He struggled with basics—tying knots, shooting a gun—things others did effortlessly, he couldn’t.

This bred a simmering resentment. Terrified of being a loser, Ted pushed himself to excel, chasing bright goals to prove his worth.

In college, he fell for a middle-class girl. It was a beautiful romance, spurring him to become a gentleman, study hard, and work tirelessly to earn cash. During this phase, he bought his dream Volkswagen—the car later used in his killings.

But the breakup shattered him. She dumped him, citing his inability to fund her lifestyle. To Ted, it was betrayal. Childhood memories of ridicule flooded back. He grew more isolated, hating everything around him.

Around then, he uncovered his origins: an illegitimate child abandoned by his mother at a chapel, spared an orphanage only because his grandfather insisted on taking him in.

To Ted, it felt like the world had turned its back on him.

That’s when he started killing.

Psychologists pegged Ted as a narcissist—excessively self-obsessed. It wasn’t a mental illness detectable by hospitals, and in the ’70s, narcissism was a nascent psychological concept.

In truth, Ted killed, raped, and tortured to satisfy himself. Records show his victims were women aged 18-25, often middle-class college students. Killing them let him exact revenge, feeling victorious as he “punished” the haughty girls who mirrored his past.

His narcissism shone through in the tapes: he narrated his murders in the third person—“He killed her, he strangled her, he hid her body…”—dodging guilt by pinning it on some detached “he,” fully aware it was himself but desperate to deceive his own mind.

At the tapes’ end, with death near, Ted showed no remorse. He blamed society, everyone else: “You people—you’ll never understand me.”

Helping the FBI Profile Serial Killers

One rare good deed in Ted’s life was aiding the FBI in profiling serial killers—not for leniency, redemption, or regret.

It began when the FBI couldn’t crack the behavioral patterns of killers like Ted or Zodiac. With serial murders surging, they built a database, interviewing murderers, believing a cunning, psychology-educated killer like Ted could illuminate their minds.

FBI agent Bill Hagmaier approached Ted openly, introducing himself as an agent crafting serial killer profiles and needing his help. Ted shot back, “Why should I help you? Don’t you want me dead?” then added, “You do too, right?”

Hagmaier replied, “I don’t enjoy it, but if my job is to flip the switch, yeah, you’re a dead man.”

Ted laughed, noting how reporters and psychologists usually feigned empathy to win him over. Hagmaier’s blunt honesty swayed him to assist, no strings attached. In truth, Ted relished being useful, superior even to the FBI. So, he helped analyze serial killer psychology, building profiles that proved invaluable—some now common knowledge today.

Lessons from Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes

After watching Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, it’s not just about understanding one of history’s most shocking cases. The series offers broader societal lessons. For me, they are:

- Never be fooled by appearances. Evil could be lurking right beside you.

- Potential criminals often bear scars from their past. To stop crime, tackle its roots.

- A small, unintended act can spark a massive crime. If Ted’s mom hadn’t abandoned him, if kids hadn’t shunned him, if his girlfriend hadn’t scorned him, maybe he’d have turned out differently.

- Stay vigilant—your life and loved ones matter most. We can’t predict when monsters emerge, so self-defense is key.

- No matter how smart or talented, everyone pays a price in the end.

- Self-control is vital. It draws the line between our animal and human sides, steering us toward good instead of evil.

In the end, Ted Bundy is just a stain on history. But from such stains, we glean lessons to build a better world. That’s not the film’s message—it’s mine, to all of you.