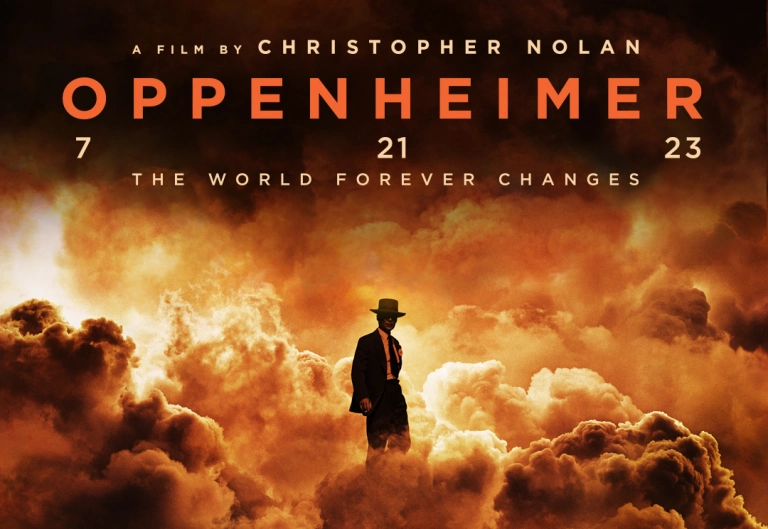

Recently, Oppenheimer has become a sensation, not only for its compelling subject—”the father of the atomic bomb”—but also for the widespread acclaim from critics. Many even call it Christopher Nolan’s greatest work to date, and it’s certainly a strong contender for the Oscars this year.

With Oppenheimer, Nolan steps away from his signature “action + mind-bending” formula to deliver a true academic drama—the kind of film many top Hollywood directors eventually pursue. While the story involves multiple timelines, it’s nowhere near as complex as Dunkirk or TENET, and the narrative is much more accessible than that of Inception or Interstellar. Still, the film leans heavily into biography, science, and politics, making it demanding for general audiences. Long dialogues, a large cast of characters, and references to the sociopolitical context of the 1940s to 1980s require a certain level of understanding. Watching Oppenheimer feels like attending a physics or political science lecture—those uninterested in such subjects may find it dry. If you seek intellectual stimulation and artistic depth, go see it. But if you want pure entertainment, action, or laughs, this may not be your cup of tea.

Note: Spoilers Ahead

Two things stood out to me most: the sound design and the visual storytelling crafted by Nolan.

Sound Design

The soundtrack can be overwhelming at times—sometimes drowning out dialogue. According to Nolan, this was intentional due to noisy on-set audio. Nonetheless, the music is deeply emotive, ranging from melancholic to heart-pounding intensity. One of the most impactful moments is the silent explosion—when the atomic bomb goes off, the world seems to pause, followed by a thunderous roar and fiery visuals that simulate the real terror of nuclear destruction. Most memorable to me was the rhythmic stomping sound (featured in the trailer), a symbolic noise that haunts Oppenheimer long after the applause fades. He’s tormented by the cheers for his “success,” knowing it led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands in Japan.

Visual Storytelling

Nolan’s visual language is bold and unconventional for a biopic. While the film could have taken a more straightforward approach like The Imitation Game or The Darkest Hour, Nolan weaves in surreal, symbolic imagery more akin to Alejandro G. Iñárritu, Darren Aronofsky, or even Martin Scorsese in Shutter Island. The editing and scripting work together flawlessly to enhance this visual style.

The film’s most emotionally charged moment comes when Oppenheimer gives a speech post-bombing, celebrated as a hero. Cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema, Nolan’s longtime collaborator, uses close-up shots with shallow depth of field to blur the background, mimicking Oppenheimer’s mental state. His facial expressions, coupled with the muted sounds and unsettling music, immerse us in his inner turmoil.

During this scene, Nolan replaces the cheers of the American crowd with screams from Japanese victims and then silence. The surreal imagery—Oppenheimer seeing the burned, disfigured dead at a celebration—reinforces his overwhelming guilt. A similar visual technique reappears during a high-stakes hearing later in the film. As tension peaks, he sees a blinding light enveloping everyone around him—a vision of what global nuclear war might look like. This fear consumes him, knowing his creation could one day destroy humanity.

Performances

Cillian Murphy delivers a phenomenal performance, deserving of an Oscar nod—and possibly the win. He perfectly captures Oppenheimer’s internal conflict: the physicist’s intellectual drive versus the crushing guilt of unleashing a monster upon the world. Murphy’s portrayal of psychological complexity is a cornerstone of the film.

Political Commentary

Notably, Nolan never shows the Hiroshima or Nagasaki bombings. Instead, he focuses on Oppenheimer’s psychological state as he awaits news from afar. He isn’t worried the bombs won’t detonate—he’s horrified that they will, and that his scientific pursuit has led to mass death.

Oppenheimer’s descent continues as he’s swept into political games, accused of communist sympathies, and blacklisted. His security clearance is revoked, and he’s subjected to relentless hearings meant to break him. Nolan uses this as a critique of political systems—how yesterday’s heroes can become today’s scapegoats. Oppenheimer is likened to Prometheus: he gave humanity fire and was punished by the gods (in this case, the U.S. government).

Personal Reflections

This part of the story may resonate more with viewers unfamiliar with Oppenheimer’s life. I made the mistake of researching him before watching the film, which diminished some surprises. Key details I had hoped to see were omitted or altered, much like my experience with The Darkest Hour. In general, to fully experience a biopic, it’s best to avoid spoilers beforehand.

Supporting Cast

In addition to Murphy, the film features an impressive ensemble: Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr., and cameos from Rami Malek and others—all delivering strong performances.

Notable Real-Life Facts Omitted or Altered

- Truman called Oppenheimer a “crybaby” in the film, but in reality, he reportedly called him a “son of a bitch.”

- Oppenheimer was politically active against the hydrogen bomb and nuclear arms race, which the film only hints at.

- He famously said, “I need physics more than friends,” and indeed had very few close companions.

- Though initially guilt-ridden, Oppenheimer later claimed scientists were like architects; what governments do with their plans is not their responsibility.

- He co-founded the World Academy of Art and Science to prevent future creations as dangerous as the atomic bomb.

- He was eventually restored to honor, awarded the Legion of Honor by France, elected to the Royal Society, and helped promote nuclear disarmament.

- He visited Japan post-war and was not met with hostility.

The Timeliness of the Film

What I admire most about Oppenheimer is its timely message. Released amid the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict and rising global tensions, the film acts as a stark warning about nuclear catastrophe. When even the father of the atomic bomb advocates for disarmament, it underscores just how terrifying these weapons truly are.

Everyone understands nuclear weapons are dangerous—but through Nolan’s storytelling, imagery, and sound, the film makes us feel that terror. We’re no longer passive observers; we’re emotionally immersed in a simulation of destruction.

Final Thoughts

To end this review, I’ll borrow the metaphor Oppenheimer shares in the film: America and Russia are like two scorpions trapped in a bottle. Either can sting the other—or both can die. But both can survive if neither acts first.

That’s why Oppenheimer is a film of our time.