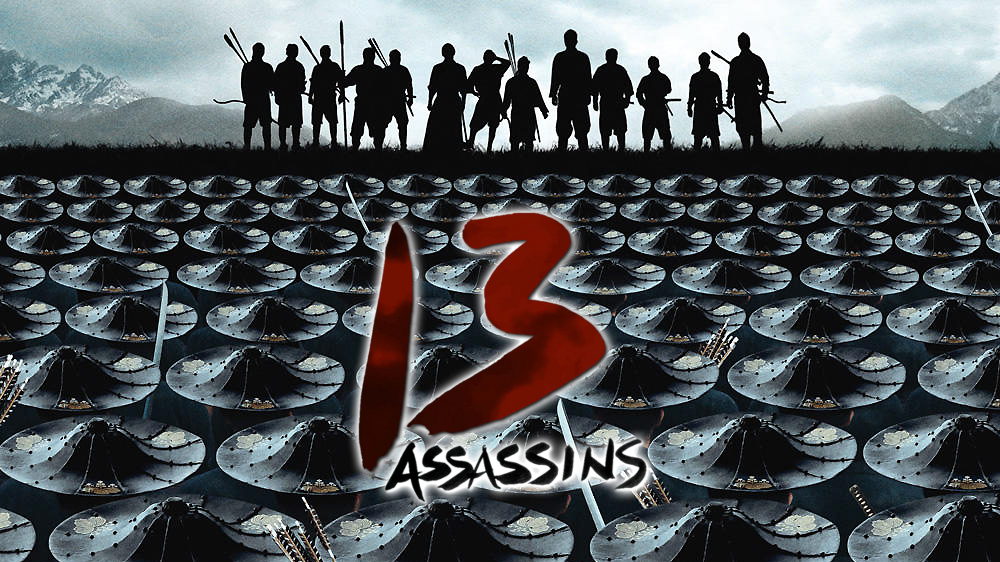

In the Land of the Rising Sun, there’s a defining trait elevated to a martial code: the samurai. Unlike mere warriors like Spartans, Vikings, or the Immortals, samurai aren’t just fighters—they embody a way of life. This code comes with strict rules, teaching not only swordsmanship but also etiquette, social norms, and the moral standards of their time. Yet, are these samurai ethics always just? Must a true samurai always follow them unwaveringly?

NOTE: THIS REVIEW CONTAINS SPOILERS

A Bloody Oath

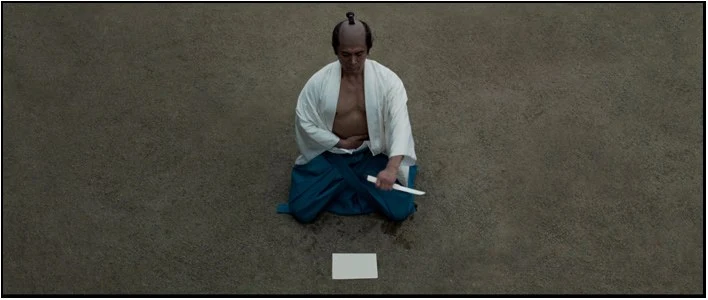

13 Assassins (Japanese title: Jûsan-nin no shikaku) opens with a striking scene: a samurai kneels before the shogunate gates, slices open his belly, and performs seppuku, the ritual suicide. This is Mamiya, a high-ranking shogunate official, taking his life in protest against Lord Naritsugu—a cruel tyrant, the shogun’s younger brother, and a potential future shogun.

Naritsugu enters the story as a young lord from the prestigious Akashi clan, a family with a long line of shoguns. Talented and handsome, he seems promising at first glance. But beneath the surface, Naritsugu is a morally corrupt savage, fearless and brutal. His hands are stained with atrocities: raping a subordinate’s wife, murdering the son of samurai Makino (who serves Lord Owari, head of three clans), and wiping out Mamiya’s entire family for daring to defy him through suicide.

His most horrifying crime? Kidnapping a beautiful village girl, bringing her to his estate, severing her arms and legs, and turning her into a twisted plaything. When he tires of her, he casts her out onto the streets—after cutting out her tongue. Later, this mutilated girl pleads her case before two shogunate officials, Shizaemon and Lord Doi, the shogun’s senior advisor. Unable to speak, she screams in rage and agony, blood streaming from her eyes. When asked how Naritsugu treated her family, she grips a brush with her mouth and scrawls a blood-soaked plea: “KILL THEM ALL.” Shizaemon later brandishes this paper as a declaration, vowing to eradicate those responsible for such evil.

A Rebellion Against the Code

Outraged by Naritsugu’s unforgivable acts, Lord Doi—the shogun’s right-hand man—and Shizaemon, leader of the guard, make a radical choice. They defy the samurai code of loyalty to their lord, assembling a team of assassins to take Naritsugu down.

Shizaemon’s actions are branded as treason against the samurai’s oath of loyalty. But to him, it’s a higher duty—to the people. If Naritsugu isn’t stopped, his reign of terror will only grow. Should he ever ascend to shogun, Japan would become a living hell.

Through tireless effort, Shizaemon recruits thirteen assassins, including himself. Most are samurai: veterans like Shizaemon and his disciple Hirayama; young blood like Ogura (Hirayama’s student) and Shinrokuro (Shizaemon’s nephew); even outsiders like Sahara, a ronin lured by 200 ryo, and Koyata, a wandering mountain hunter with no home. Together, they embark on a suicide mission: to kill the powerful Lord Naritsugu, guarded by hundreds of Akashi clan samurai.

The Loyal Foe

Naritsugu’s side would be unremarkable if not for Hanbei, the head of his guard. A samurai as renowned as Shizaemon, Hanbei trained in the same dojo and sees Shizaemon as a lifelong rival. Skilled, humble, and cunning, Hanbei admits to always trailing behind Shizaemon, viewing him as the most formidable threat if he turns against the lord. Hanbei even visits Shizaemon’s home alone, preaching loyalty in a bid to dissuade him.

Sadly, Hanbei is a traditionalist, placing loyalty above all else in the samurai code. Though he knows Naritsugu’s cruelty—having failed to stop him from slaughtering Mamiya’s family—and recoils at Naritsugu’s dream of plunging Japan back into warring states as shogun, Hanbei remains steadfastly loyal to his last breath. This pits him against Shizaemon, who prioritizes justice for the people and nation over blind allegiance, setting two honorable samurai on a collision course where only one can survive.

Echoes of a Classic

With its premise of a samurai band assembling, using traps and a village’s defenses to fight a larger force, and ending in heroic sacrifice, 13 Assassins recalls Akira Kurosawa’s timeless Seven Samurai. It clearly draws inspiration from the classic, with nods in several scenes, but it’s no mere Seven Samurai 2.0. Distinct messages give 13 Assassins its own soul. While Seven Samurai celebrates selfless warriors protecting the poor from bandits during the Warring States period, 13 Assassins is set in the peaceful Edo era, exploring a samurai’s duty to justice—breaking the code of loyalty to defy a tyrannical lord.

Modern Thrills, Timeless Depth

One edge 13 Assassins has over Seven Samurai for today’s viewers is its action. Made in 2010, it outpaces the 1954 classic with gripping, samurai-style combat and clever defensive tactics—traps and strategies that captivate fans of high-stakes thrills over dialogue. That’s not to say it skimps on substance. The story and dialogue carry weight, especially in two standout exchanges where Shizaemon and Hanbei debate the samurai code: what matters more, loyalty or righteousness?

A Crowded Cast

The film boasts a large ensemble, which might overwhelm first-time viewers. It’s not until two-thirds in that you start tracking the characters, picking out standouts like Shizaemon, Hanbei, Naritsugu, Hirayama, Shinrokuro, and Sahara. The rest fade into the background, hard to recall unless you rewatch it a couple of times.

The Unforgettable Villain

For me, the most striking character isn’t Shizaemon or Hanbei—central and vital as they are—but Naritsugu, the film’s antagonist. He’s no typical tyrant like Qin Shi Huang or Hitler, nor a conquering hero like Alexander the Great. Young, skilled (a master of sword and bow), and dashing (so handsome you might mistake him for the hero at first), Naritsugu is utterly unique. His uniqueness lies in his cold-blooded brutality, paired with chillingly rational justifications rooted in the samurai era—logic so twisted yet fitting that his peers can’t argue back.

In Naritsugu, you sense a boredom so deep it drives him to evil. Born into privilege, handed power too soon and too easily, he’s a ruined shell of what could’ve been a gifted youth. When he learns of the assassination plot, he doesn’t panic—he revels in it, declaring war “exciting” and vowing to drag Japan back to chaos as shogun. Fear only grips him when a blade pierces his gut, unprotected for the first time, death’s breath hot on his neck. Even then, as he dies, he calls it the most thrilling day of his life. Naritsugu breaks the mold of a stock villain—infuriating, pitiable, a tragic figure as if cruelty chose him, not the other way around.

A Window to Edo Japan

The film’s setting deserves praise too. Shot in 2010, it captures the Edo period’s essence—sliding doors, paper walls adorned with aristocratic patterns, and a small, impoverished village turned into a blood-soaked battleground where twelve of the thirteen fall. This meticulous design earned 13 Assassins a 2011 Asian Film Award for Production Design.

Beyond action and meaning, the film offers a rich slice of Japanese culture. It stays true to Edo-era customs: samurai with shaved heads, women with plucked brows, whitened faces, and blackened teeth—beauty standards jarring by today’s measure. Unlike flashier samurai films like Rurouni Kenshin or Takashi Miike’s own Blade of the Immortal, which lean into fantasy, 13 Assassins opts for historical fidelity, boosting its cultural and historical heft.

A Modern Classic

All in all, 13 Assassins is phenomenal—to me, the second-best samurai film after Seven Samurai. It earns its place among Japan’s samurai classics. Yet, despite being a samurai tale, its core message is boldly “anti-samurai”: should the code prize duty to justice over loyalty? It’s a daring, tradition-shattering idea— upset—modern, deeply humane, and thought-provoking.